THE SECESSIONIST POSTERS FROM REVOLUTION TO THE AVANTGARDE

Pallas Athena witnessed the battle of Theseus and the Minotaur, a dynamic and impassioned clash that played out under the impartial gaze of the Goddess of the Arts, although nobody would be at all surprised if she was rooting for the handsome hero deep down. This is the subject of the first poster that Gustav Klimt created to publicise Ver Sacrum, the official magazine of the Vienna Secession. A bold and striking choice: a symbolic battle in which the modern artist tackled a stagnant environment that had fallen far behind the times, the Academy of Arts. It was a declaration of intent, conveyed via that exceptional means of expression and communication: the Affiche.

This is an impressive example, but it is by no means the only one. The Secessionist posters are among the most important of their age, thanks to the clever and intuitive decision to send a revolutionary message via the particularly appropriate means of public propaganda. The aim was to produce universal and collective art, but it immediately became clear how much social impact the poster would acquire by conveying national and international ideas and messages.

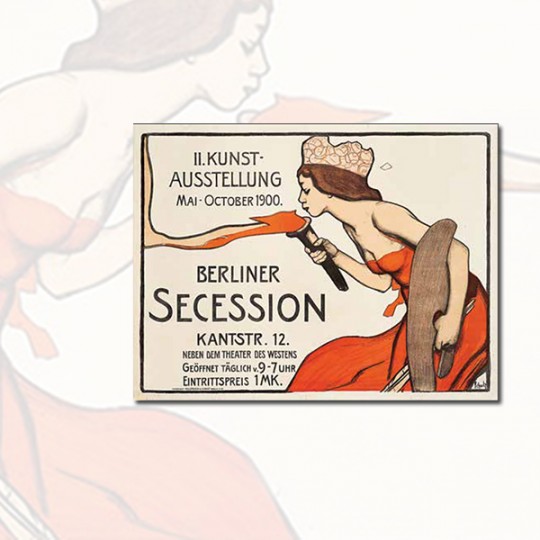

The Secessionists played a vital role in artistic development in general, not to mention their influence on the typographical panorama in central European, to the extent that the works from those years still provide an emblematic insight into their ideas and artistic taste and represent a unique and irreplaceable document in the history of the affiche. The Secessions were young, dynamic movements free of dogma and cold academic mandates, where artists could master their own language, a definite social role and a whole new commitment to communication. These movements found fertile ground for change in Austria and Germany: Munich was the pioneer of this radical movement in 1892, Vienna was flooded with anti-academy feeling in 1897 and it was Berlin’s turn the year after. But how were they to spread their message? The answer came from Paris, the city of light, the catalyst for an irresistible cultural dynamism that also invested in communication. And Paris was also the city that invented the affiche, ça va sans dire.

Our Twentieth Century Art auction proved that affiches from Secessionist circles continue to have an incredible appeal in international collectors’ circles. It is no surprise that the small lot up for auction attracted such a large number of enthusiasts: each piece was a graphic statement of intent created by illustrious artists. It is impossible not to appreciate Schulz’s Muse or not to recognise the Secession palace by Jettmar. Or again not to lose oneself in the melancholy liquid gaze of Kokoschka, one of Klimt’s young students, a rebel among rebels, increasingly driven towards a certain expressionism that shook off any symbols to become pure, indecent, psychotic emotion.

This is the same inner nature that emerges in the final secessionist poster by Egon Schiele, who depicted himself sat at a table surrounded by fellow artists to emphasise the solidarity that was such an integral part of the group, marking the start of an intimate image more similar to his style and interior world. A changed world, a reflection of the post-war period, in which artists also began to discuss new directions. In this very work, the last he would ever make, Schiele laid the foundations for passing the baton on to the modern Avantgarde.

by Francesca Benfante

THE DEPARTMENT