A BANK FOR ITALY

In 1861, the time of the Kingdom of Italy’s founding, paper money was provided by local banks linked to the governments of the Former States, which operated in different ways according to different laws and customs. Among these, only the Banca Nazionale negli Stati Sardi and the Banca Nazionale Toscana issued genuine banknotes convertible into coins (i.e. gold), while the other banks put cash vouchers and legal tender of various forms into circulation that, even when they were issued to the bearer, could only be cashed if they were endorsed—similar to today’s bank checks. It was quite obvious that the Banca Nazionale negli Stati Sardi, upon extending the Kingdom of Sardinia’s institutions to the newly formed Kingdom of Italy, aspired to establish itself as a state bank for the entire country and, in fact, apparently with this aim, in the first years after unification, it rushed to open branches in many of the peninsula’s cities.

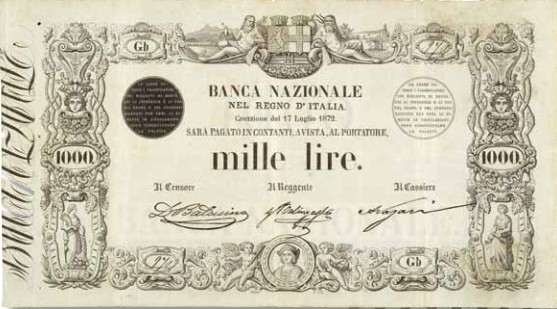

A bill for the merger of the Banca Nazionale negli Stati Sardi and the Banca Nazionale Toscana, with the consequent creation of a new institution, to be named Banca d’Italia and to be in charge of issuing paper money and assuming the role of Treasury of the State, was presented in Parliament in 1865; but it didn’t move forward due to the hostility of the Tuscan deputies, who were able to bring colleagues from the southern provinces over to their side. Given the size of the obstacle blocking its ambitions, the Banca Nazionale negli Stati Sardi adopted a strategy made up of small steps: they continued to open branches throughout the territory of the Kingdom, but less aggressively, and worked to quietly take on the name of the Banca Nazionale nel Regno d’Italia. Thus, without formal measures or resolutions, this new name began to creep into the terminology adopted by ministerial bureaucracies for the preparation of its acts and, in a few years, had its final, public, in a manner of speaking, christening, by appearing on the front of banknotes. At the recent auction of December 2013, four rare banknotes bearing witness to this smooth transition from one name to another were put up for sale.

Specimens of 1,000-lira notes (the highest value permitted to be issued at the time) at first glance seem the same, but upon closer look, the name of the issuer on the upper portion of the note varies. In particular, on the banknote issued 22 July 1868, the name is still Banca Nazionale negli Stati Sardi, while on the banknote of 17 July 1872 it is already Banca Nazionale nel Regno d’Italia, the same as with the last two lots that make up the magnificent quartet, both issued on 15 January 1873. The extreme rarity of these notes is explained by their face value: each was theoretically convertible into coined gold that weighed about 322 grams, which, at the time, was ten times the weight of a 100-lira gold coin, which is 32.25 grams. As for the story of the Banca d’Italia, after the project failed in Parliament in 1865, for several years nothing else happened until the 1892 Banca Romana scandal exploded; the first great episode of connivance of malfeasance and politics in Italian history. The severity of the episode forced the government to take the bull by the horns, forcing the merging of all issuing banks within the Banca d’Italia, which finally was born in 1893.

By Carlo Barzan

A bill for the merger of the Banca Nazionale negli Stati Sardi and the Banca Nazionale Toscana, with the consequent creation of a new institution, to be named Banca d’Italia and to be in charge of issuing paper money and assuming the role of Treasury of the State, was presented in Parliament in 1865; but it didn’t move forward due to the hostility of the Tuscan deputies, who were able to bring colleagues from the southern provinces over to their side. Given the size of the obstacle blocking its ambitions, the Banca Nazionale negli Stati Sardi adopted a strategy made up of small steps: they continued to open branches throughout the territory of the Kingdom, but less aggressively, and worked to quietly take on the name of the Banca Nazionale nel Regno d’Italia. Thus, without formal measures or resolutions, this new name began to creep into the terminology adopted by ministerial bureaucracies for the preparation of its acts and, in a few years, had its final, public, in a manner of speaking, christening, by appearing on the front of banknotes. At the recent auction of December 2013, four rare banknotes bearing witness to this smooth transition from one name to another were put up for sale.

Specimens of 1,000-lira notes (the highest value permitted to be issued at the time) at first glance seem the same, but upon closer look, the name of the issuer on the upper portion of the note varies. In particular, on the banknote issued 22 July 1868, the name is still Banca Nazionale negli Stati Sardi, while on the banknote of 17 July 1872 it is already Banca Nazionale nel Regno d’Italia, the same as with the last two lots that make up the magnificent quartet, both issued on 15 January 1873. The extreme rarity of these notes is explained by their face value: each was theoretically convertible into coined gold that weighed about 322 grams, which, at the time, was ten times the weight of a 100-lira gold coin, which is 32.25 grams. As for the story of the Banca d’Italia, after the project failed in Parliament in 1865, for several years nothing else happened until the 1892 Banca Romana scandal exploded; the first great episode of connivance of malfeasance and politics in Italian history. The severity of the episode forced the government to take the bull by the horns, forcing the merging of all issuing banks within the Banca d’Italia, which finally was born in 1893.

By Carlo Barzan